Graphic novels: Drawing on peacebuilding

Fair laws and legitimate, accessible, effective legal institutions are crucial to peacebuilding. They define appropriate social behaviour, protect rights, limit power, and hold accountable those who abuse it. Laws and legal institutions provide frameworks and mechanisms for non-violent dispute resolution and address underlying grievances. They prevent the re-emergence of violent conflict, further reconciliation and incentivise peaceful collaboration.[1]

However, laws and legal institutions are also tools in the hands of the powerful. They are biased and politicised, used to entrench inequalities, discrimination and marginalisation. Laws and legal institutions search for, and claim to establish, the one objective truth about an act of violence to define a wrong, establish with certainty who the victims and perpetrators were, punish the perpetrators, and deter future harm.[2]

However, the truth of laws and legal institutions is just the official story. It rarely fully captures the nuances and complexities of collective, group-based grievances, often against exclusive political regimes. The official story does not fully address survivors’ experiences of conflicts. Consequently, the legal truth does not educate and empower in a context-sensitive way. And laws and legal institutions do not provide adequate redress and create justice that contributes to sustainable peace.[3]

Graphic novels – pieces of sequential art that consist of images and usually words [4] – offer alternative stories that are openly subjective and understand themselves as one of many accounts of violent acts. They are more nuanced than legal stories, convey complex experiences that are not always representable in law, and offer socio-cultural and moral insights. Therefore, they make the invisible visible, challenge the legal discourse, and inspire more adequate and just outcomes for survivors. Beyond that, graphic novels challenge a wide readership to try and understand events, to identify and confront intolerance and injustice, and to act for a better, more peaceful world.[5]

However, as Frank Möller and Rasmus Bellmer highlighted in a previous post on this blog,[6] images, including those in graphic novels, can also perpetuate accepted and taken for granted ideas about war and peace and confirm what they set out to challenge. Just like laws and legal institutions, they can simplify and essentialise, reinforce invisibilities and fuel the fires of ignorance. In the search for justice, we also have to ask if and how graphic novels, and any form of representation, can do justice to a violent past.

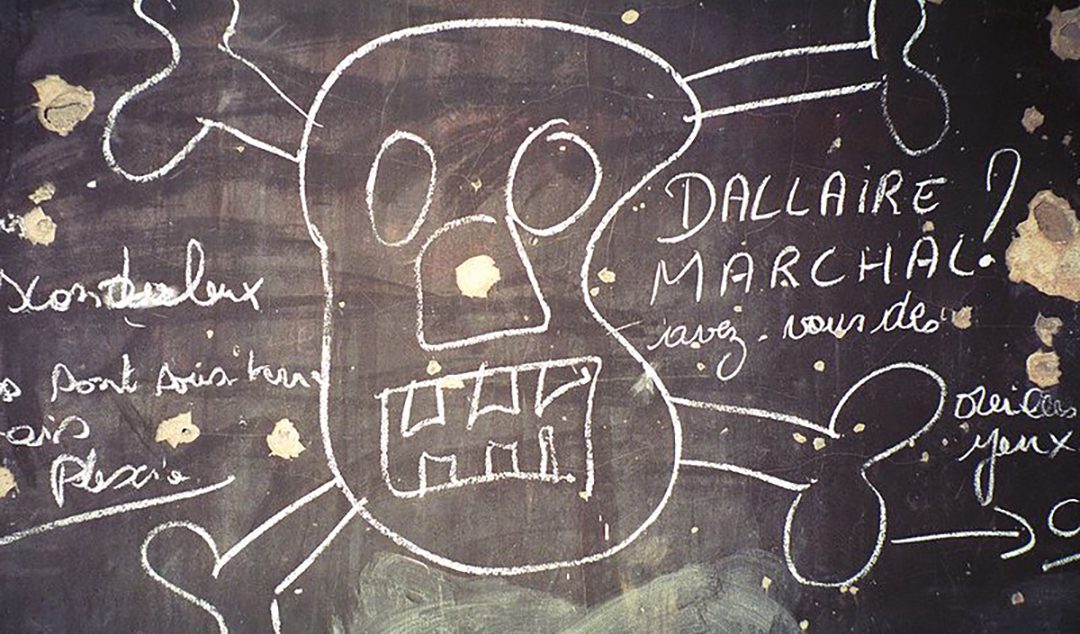

Take Jean-Philippe Stassen’s graphic novel Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda as an example.[7] It deals with the Rwandan genocide by describing the life of the teenage Hutu boy Deogratias, who witnessed and perpetrated the rapes and killings of his Tutsi friends and love interests Apollinaria and Benina, and their mother Venetia.

However, unlike domestic and international courts, the graphic novel does not focus on the atrocious events in April 1994. Instead, the storyline before the genocide contextualises them and centres on relationships between the characters. In addition to Deogratias, Apollinaria, Benina and Venetia, there is Prior Brother Stanislas, allegedly Venetia’s former lover or client and the father of Apollinaria. The Belgian priest Brother Philip joins Prior Brother Stanislas in Rwanda to work in the church and becomes a friend to the teenagers and possibly has a crush on Apollinaria. There is also the French army sergeant who tries to befriend Deogratias and uses the sexual service of Venetia. Augustine is a Twa childhood friend of Venetia who proposes to her but is turned down. Julius is a Hutu extremist who participates in the genocide together with Deogratias. And Bosco is a soldier in the Rwandan Patriotic Front whom Deogratias meets after the genocide when he returns from what today is the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In the aftermath of the genocide, Stassen emphasises the consequences and effect of Deogratias’ actions. He is traumatised, ridiculed and isolated and copes by drinking. Stassen also highlights difficulties regarding reconciliation. Deogratias poisons the French sergeant, Bosco and Julius possibly because of their involvement in the rapes and killings of Apollinaria, Benina, Venetia and Augustine, or maybe because of their knowledge of Deogratias’ role in it.

Based on months of investigative journalism in Rwanda, Stassen shows how and why the genocide was committed, its wider context and enabling environment, the dynamics and consequences of atrocity crimes, including the costs of surviving. This way, he facilitates an alternative, more nuanced understanding of survivors’ experiences.[8] In doing so, he challenges legal understandings of responsibility and punishment.

Chronologically fluid storytelling enables Stassen to highlight that the Rwandan genocide did not just suddenly erupt and yet was not a causal consequence of a linear history. The graphic novel demonstrates that the Rwandan genocide took place against the background of colonial violence, centuries of tension, and large-scale, deliberate and frequent discrimination against Tutsi at least since the 1970s. Nevertheless, it was not an inevitable consequence of this history.

Deogratias explores the dynamics of the Rwandan genocide, starting by challenging some aspects of the (legal) understanding of ethnical groups in the Rwandan context. In tracing the history of Venetia’s family, the graphic novel speaks to the (legal) notion that membership in ethnical groups is allocated through lineage and can easily be determined based on physical characteristics. However, by centring diverse inter-ethnic relationships, it suggests that no clear boundaries existed between Hutu, Tutsi and Twa. The continuous reinvocation of ethnicity only by White characters in the story indicates that they are colonial constructs. Colonists created Hutu, Tutsi and Twa as ethnical groups and categorised Rwandans accordingly based on physical differences such as skin colour and hight, and enshrined those differences in law. Neo-colonialists employ the same frame to understand Rwanda centuries later. This way, the graphic novel hints at the racist logic that made the Rwandan genocide possible. The discriminatory behaviour of the French sergeant and the ineffective resistance and subsequent flight of Prior Brother Stanislas and Brother Philip reveal the cowardice and culpability of the international community and the Church that have not been addressed at least by international courts.

Furthermore, Julius’ gang of Hutu extremists shows that genocidal acts are not perpetrated by a single individual but by groups of people. This challenges especially international courts that only focus on the individual criminal responsibility of those most responsible for acts of collective violence. They create the false impression that catching the big fish and pulling them out of the sea addresses and redresses the structural inequalities that led to violence. However, Deogratias’ life after the genocide shows that marginalisation persists and continues to fuel violence. Deogratias is traumatised by the genocide and experiences social exclusion, homelessness and alcohol addiction and is the victim and perpetrator of acts of direct violence by and against members of his community. This shows that imprisoning the masterminds of genocide and leaders of (civil) war does not address the underlying grievances that led, and still lead, to acts of violence. The graphic novel highlights that a more holistic response that goes beyond the law and legal institutions is necessary.

Also unlike courts, the graphic novel does not focus on acts of genocidal violence. This means that it misses the opportunity to address their consequences for victim-survivors in a graphic novel format, circumventing the question of how to represent the unrepresentable. However, the protagonist Deogratias allows Stassen to make visible the generally underrepresented and legally overlooked effect the genocide had on perpetrators. In court, this might come up in discussions of mitigating circumstances that largely leave the victim-perpetrator dichotomy intact (although, cases like the one against Dominic Ongwen currently before the International Criminal Court are interesting in this context). [9] In Deogratias, in contrast, it is a central theme and, drawing on Hannah Arendt’s observations of the Eichmann trial[10], Stassen highlights that Deogratias is an ordinary human who acted extraordinarily in extreme circumstances. While in the story this does not absolve him of his moral, if not legal, responsibility for his actions, it highlights that the distinction between victims and perpetrators is not clear cut.

In exploring the complex aftermath of the Rwandan genocide and its impact on Deogratias, Stassen complicates who can or should be held responsible for acts of genocide and calls carceral responses to crimes into question. He highlights the need for more holistic approaches that include context-sensitive psychosocial work and community education to tackle structural inequalities to enable sustainable peace.

Deogratias suggests that responses to genocide that might be more successful for reconciliation, and consequently peace, have to be inclusive and involve perpetrators. They have to be targeted and sensitive to the complexities of the circumstances in which specific genocidal acts were perpetrated. They need to follow a flexible approach to legal conceptions of guilt and innocence without allowing impunity.

Additionally, to be truly just, responses to genocide have to investigate the role of all parties involved and hold them responsible for the actions and inactions. White skin does not give a carte blanche.

[1] peacebuildinginitiative, ‘Introduction: Justice, Rule of Law & Peacebuilding Processes’

[2]Hannah Baumeister, ‘Drawing on Genocide’ (2019) 13(1) Law and Humanities 3.

[3] ibid.

[4] Will Eisner, Comics and Sequential Art: Principles and Practices from the Legendary Cartoonist (Poorhouse Press 1985) 5; Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (Harper Perennial 1994) 7.

[5] Rose Brister and Belinda Walzer, ‘Kairos and Comics: Reading Human Rights Intercontextually in Joe Sacco’s Graphic Narratives’ (2013) 40(3) College Literature: A Journal of Critical Literary Studies 138 Courtney Donovan and Ebru Ustundag, ‘Graphic Narratives, Trauma and Social Justice’ (2017) 11(2) Studies in Social Justice 221; Thomas Giddens, ‘Comics, Law, and Aesthetics: Towards the Use of Graphic Fiction in Legal Studies’(2012) 6(1) Law and Humanities 85; Thomas Giddens, ‘What is Graphic Justice?’ (2006) The Comics Grid: Journal of Comic Scholarship 14; Jérémie Gilbert and David Keane, ‘Graphic Reporting: Human Rights Violations through the Lens of Graphic Novels’ in Thomas Giddens (ed) Graphic Justice: Intersections of Comics and Law (Routledge 2015); Gretchen Schwarz, ‘Graphic Novels, New Literacies, and Good Old Social Justice’ (2010) The Alan Review 71; Jessica Silva, ‘“Graphic Content”: Interpretations of the Rwandan Genocide Through the Graphic Novel’ (2009) Master of Arts thesis, Department of History, Concordia University 4-5, 31, 43.

[6] Frank Möller and Rasmus Bellmer, ‘Peace videography: visual tools for mediation and peace-building’ (HCPB, 12 October 2020)

[7] (Alexis Siegel tr, First Second 2006).

[8] Jérémie Gilbert and David Keane, ‘Graphic Reporting: Human Rights Violations through the Lens of Graphic Novels’ in Thomas Giddens (ed), Graphic Justice: Intersections of Comics and Law (Routledge 2015); Sara Mortensen, Lars Soderbergh, and Jared Christensen, ‘Deogratias and the Representation of the Rwandan Genocide’ (30 May 2012)

[9] See, for example, International Criminal Court, ‘Ongwen Case’

[10] Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (Viking Press 1963).