By Jean-Claude Kayumba (University of Sheffield)

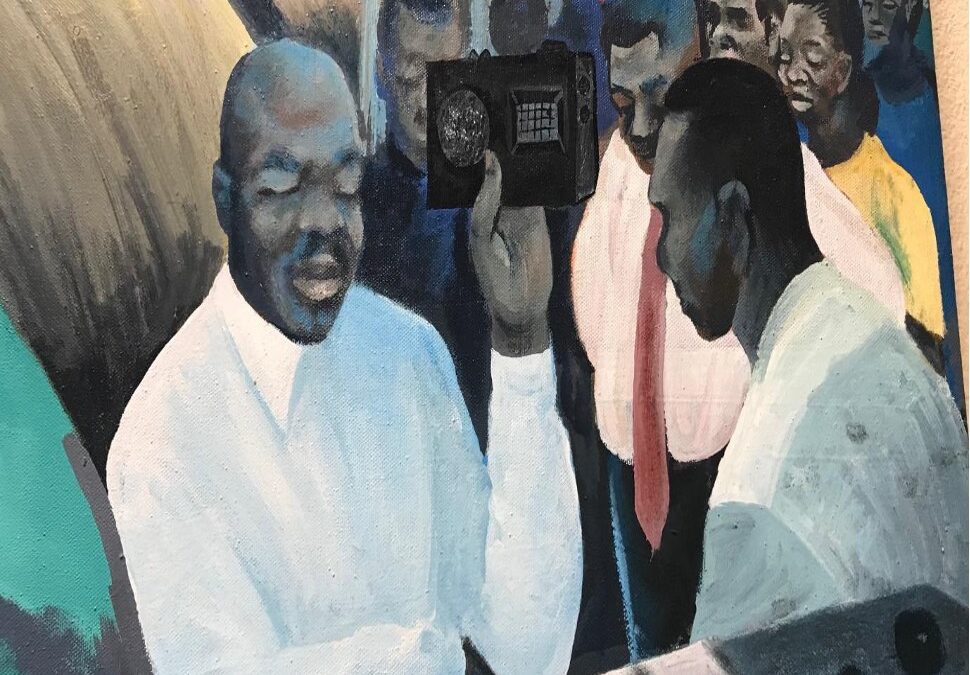

Paint by Cheri-Cherin for Radio Okapi’s expatriates leaving staff (2007)

Radio plays a significant role in trying to reconcile a divided society, empowering its citizens for a better future. While in some parts of the world the role of radio is not what it used to be, radio is still high in demand in other parts of the globe (Jacob, 2017). Despite being the oldest form of broadcasting, and despite the emergence of new types of media, radio with its various characteristics has maintained its place in society, particularly within peacebuilding circumstances (Heywood, 2018). The affordability of radio and its ability to serve both remote rural and metropolitan communities make radio highly suited to African social usage (Gunner et al., 2011). Whereas UN radio, operating within conflict regions, was traditionally used as a supportive tool to achieve free election, and as a tool to inform the local populations affected by war about the activities of the peacekeeping mission on the ground, the role of the radio within post-conflict has evolved. There is now a growing and pressing need for the radio to assist in rebuilding a broken civil society (1) through radio news and through radio interventions.

The case of Radio Okapi in the Democratic Republic of Congo resonates with the main argument of this writing. This reflection draws on several interviews conducted with the first employees of RO, and on a qualitative content analysis of dozens of RO’s radio interventions.

- The case of Radio Okapi

Radio Okapi is a solid example evidencing the crucial role of the radio within (post-) conflicts contexts. The DRC went through a period of intense war between 1998 and 2003. On 30 November 1999, the DRC UN peacekeeping mission (MONUC, today MONUSCO) was created with the initial aim of observing the upholding of the Lusaka ceasefire agreement (2). However, the ongoing war brought new developments on the ground. Millions of innocents were killed. The mission was forced to expand. This expansion also included the creation of a new radio station to support the UN mission. The UN peacekeeping mission decided to enter in a partnership with an external partner organisation – the Hirondelle Foundation (3) – which had extensive expertise in setting up radios within post-conflict contexts. The two partners agreed on an “ambitious plan to use the airwaves to unite a vast country (4) wrecked by killing, kidnapping, rape and disease” (Bakody, 2017:33). This marked the beginning of the implementation of a local/indigenous peacebuilding approach. On 25 February 2002, a new radio station calling itself “the frequency of peace” – Radio Okapi – was created in the DRC. The peacebuilding objective of this new radio station was clearly symbolised in its name, Radio Okapi. The okapi is a shy and peaceful animal found in the rainforests of the Congo region (Britannica, 2022). Okapi was the name chosen (5) because this antelope-like docile animal unique to the DRC was seen by many indigenous in the Congo as a symbol of peace.

- Radio interventions rebuilding the DRC civil sphere.

Within a changing political landscape, RO has been exercising a strong civil society construction agency in their daily assignment, rebuilding a civil society destroyed by years of civil war, and kept silent for numerous decades. Special space was created for the most deprived and marginalised of the DRC civil sphere. I now take the most salient categories (from a non-exhaustive list) in turn.

2.1 Women

Promoting the wellbeing and inclusion of women through radiocasts was a vital part of the DRC civil sphere reconstruction project. Its importance was linked to two main factors. First, it was because in the DRC (African) society women are generally marginalised and unfairly disempowered even though they are key stakeholders in all the aspects of daily life. Women require more information about their rights, and a greater voice in society (Heywood and Ivey, 2022). To support this view, reference can be made to one of RO’s callers who argued that “this is not the time yet to trust women with huge and important responsibilities in a country as big as the DR Congo”. More interestingly, some of the staff of RO held those kinds of views at the outset of the radio station as this study has uncovered. In second, it was important in war contexts where women are collateral victims of different militia, rebels, governmental troops and even of some undisciplined UN peace soldiers. Rape has been weaponised in all (armed) conflicts in DRC. A UN official called DR Congo ‘rape capital of the world’. DR Congo is ‘the worst place on earth to be a woman’ (The Guardian, 2011). In these tragic contexts it was a positive action for RO to organise different programmes they did exclusively for females. These kind of broadcasts by RO played a significant role not only in giving a voice to voiceless women, but further, in educating the general population (men?) in seeing women not as ‘second-class’ human beings, but as full members of society. These programmes of RO reframed the structure of the DRC civil society by insisting that defending that women could also bring a vital contribution to the reconstruction of the post-conflict nation.

2.2 The Youth

When it comes to peacebuilding in Africa, young people have always played a central role (Bangura, 2022). The Hirondelle Foundation’s manual, Practice of Journalism in Conflict Zones (p.10) specifies that RO listeners are mainly young. The history of young people in the DR Congo has been challenging. High numbers of young people – including underage children – have engaged in militia. In fact, “the lack of social opportunities during the war had led many young Congolese to turn to militias as the only source of social mobility” (Van Acker and Vlassenroot 2000:25), and “these social motivations persisted after the war” (Autesserre, 2006:13). One of the objectives of RO in supporting this specific component of the Congolese civil society was attempting to disengage these young persons from war and diverse illegal activities, especially the underage ones. My analysis has unveiled that RO broadcasts, but especially those targeting the youth, had a pedagogical objective before anything else. Educating both the youth and the general population (listeners).

2.3 Geographically and socially marginalised

Some years ago, when RO initially commenced its work (2002), the country was divided in several parts. Some parts of the country were controlled by the central government, and others by different rebel groups. There was no communication between different parts of the country. As an illustration, for one in the capital to reach some parts of the country, they had to transit through neighbouring country (e.g.: going through Uganda to reach the Eastern part of the DRC). The majority of the population was marginalised. Not only geographically, but also socially. Here, being marginalised socially is understood as “exclusion to privileges” unjustly reserved to a minority by default or by force, no matter the geographical location. RO attempted to reunite the country of geographically and socially secluded individuals/communities.

First, the geographically marginalised. From its genesis, RO established studios all over the massive DRC, even in parts controlled by rebel groups. Further, RO established the strategy of broadcasting in four national languages (4) and in French. Listeners were allowed to bring in their comments in their native dialects. The analysis of 45 broadcasts of RO has shown a strong consistency with regard to the participation of listeners/callers from secluded areas of the DR Congo. On each transmission, the analysis has shown a great diversity of the geographical location of callers.

Second, the socially marginalised. When reaching those geographically secluded, what was unique with RO’s radio interventions was that they were contacting people seen as the forgotten of the Congolese society such as shoemakers, etc. Guided by their understanding of civil society, RO did not see the State or the Market (powerful businessmen/businesswomen/companies) as being their sole qualified guests but handed their microphone to everyone in society, irrespective of any consideration such gender, age, social class, political appurtenance, etc.

Conclusions

This blog has succinctly considered the crucial role of radio stations within post-conflict circumstances The UN radio stations of the past had different roles: informing local populations of their missions, (e.g. vaccination programmes, education programmes, etc.), preparing populations for free and fair elections, etc. When the UN and the Hirondelle Foundation entered into a partnership, they generated a different and exclusive type of radio station, Radio Okapi. Drawing on the example of RO, the study conducted and reported in this blog provides indications that the role of the radio within post-conflict contexts (especially within African circumstances where radio is still the dominant medium) has expanded beyond the traditional roles evoked above, navigating more towards “assistance in civil society (re-) building”. I have considered the way this role has effectively changed from a traditional earlier one. RO has made a vital contribution to reconciling the broken civil sphere of the DRC. It has done this through an inclusive, gender-sensitive and informative approach that has sought to empower its listeners and reduce conflict.

Notes.

- I define civil society in Alexandrian terms (2006:31) as “both a normative and real concept because it is a sphere of solidarity in which individuals’ rights and collective obligations are tensely intertwined”

- The Lusaka Agreement between the countries of Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Namibia, Uganda, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe, seeks to bring an end to the hostilities within the territory of the DRC. It addresses several issues including the cessation of hostilities, establishment of a joint military commission (JMC) comprising representatives of the belligerents, withdrawal of foreign groups, disarming, demobilising, and reintegrating of combatants, release of prisoners and hostages, re-establishment of government administration and the selection of a mediator to facilitate an all-inclusive inter-Congolese dialogue. The agreement also calls for the deployment of a UN peacekeeping force to monitor the ceasefire, investigate violations with the JMC and disarm, demobilise, and reintegrate armed groups (UN-Peacemaker, 1999).

- The Hirondelle Foundation is a Swiss non-profit organisation founded in 1995, which provided information to populations faced with crisis, empowering them in their daily lives and as citizens. The HF has great expertise in setting up radios in conflict zones.

- The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo or simply the Congo, and historically Zaire, is the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa, the second largest in all of Africa (after Algeria), and the 11th-largest in the world. With a population of around 90 million, the Democratic Republic of the Congo is the most-populous Francophone country in the world, as well as the 4th-most populous country in Africa (after Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Egypt), and the 13th-most populous country in the world (mapfight.xyz/DR Congo is 0.23 times as big as Western Europe).

- Local populations were asked to vote on a name for the new radio station. Okapi was chosen by the great majority of those involved in the process.

References

Autesserre, S. (2006). Local violence, national peace? Postwar “settlement” in the Eastern D.R. Congo (2003–2006). African Studies Review, 49(3), 1–29. doi:10.1353/arw.2007.0007.

Bakody, J. (2017). Radio Okapi Kindu: The station that helped bring peace to the Congo; A Memoir. Group West Publishers.

Bangura, I. (2022). Youth-Led Social Movements and Peacebuilding in Africa. Taylor & Francis.

Britannica (2022). Okapi. Available online at https://www.britannica.com/animal/okapi.

Gunner, E., Ligaga, D. and Moyo, D. (2011). Radio in Africa: Publics, Cultures, Communities. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Heywood, E. (2018). Increasing female participation in municipal elections via the use of local radio in conflict-affected settings: the case of the West Bank municipal elections 2017. Journalism. View this article in WRRO

Heywood, E. and Ivey, B. (2022). Radio as an empowering environment: how does radio broadcasting in Mali represent women’s “web of relations”? Feminist Media Studies, 22(5), pp. 1050–1066. doi:10.1080/14680777.2021.1877768.

Jacob, J. (2017). Convincing Rebel Fighters to Disarm – UN Information Operations in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

The Guardian (2011). ‘Forty-eight women raped every hour in DR Congo, study finds’. Available online at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/may/12/48-women-raped-hour-congo.

Van Acker, F., & Vlassenroot, K. (2000). Youth and conflict in Kivu: ‘Komona clair’. Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, 1-17.